One hundred and fifty years ago today, a tall thin man, weak and dizzy from an as yet undiagnosed case of smallpox, rose from a temporary platform to face a crowd of onlookers beneath a cold and drizzly gray sky. He was there to deliver “a few remarks” in dedication of an as yet unfinished cemetery. The previous speaker was Edward Everett renowned orator and the the main featured attraction that bleak morning.

One hundred and fifty years ago today, a tall thin man, weak and dizzy from an as yet undiagnosed case of smallpox, rose from a temporary platform to face a crowd of onlookers beneath a cold and drizzly gray sky. He was there to deliver “a few remarks” in dedication of an as yet unfinished cemetery. The previous speaker was Edward Everett renowned orator and the the main featured attraction that bleak morning.

The nation was some two and a half years into the bloodiest and most ghastly war this country has ever fought. Reeling from seemingly unending blood and gore, the nation was weary. Surely nothing could be worth this horrible loss, could it?

Edward Everett began his oration and did not finish displaying his oratorical extravagance for some two hours. One can only imagine how those in the crowd of listeners must have tired over that time, standing outside in the damp, chilly Pennsylvania air. For two hours Edward Everett went on, describing in intricate detail and with great dramatic flourish every aspect of the mighty battle that had raged across there for three long and bloody days the previous summer. The battle had left so many dead that a final resting place had been made locally to house them since transportation home for such a number of corpses was impossible. Though more had died in a single day at the battle known simply to soldiers as Antietam, in Pennsylvania, more than 50,000 men gave their lives over the three day engagement, making it the bloodiest single battle of the entire war. The country was tired, weary and wanting the war to end.

Edward Everett began his oration and did not finish displaying his oratorical extravagance for some two hours. One can only imagine how those in the crowd of listeners must have tired over that time, standing outside in the damp, chilly Pennsylvania air. For two hours Edward Everett went on, describing in intricate detail and with great dramatic flourish every aspect of the mighty battle that had raged across there for three long and bloody days the previous summer. The battle had left so many dead that a final resting place had been made locally to house them since transportation home for such a number of corpses was impossible. Though more had died in a single day at the battle known simply to soldiers as Antietam, in Pennsylvania, more than 50,000 men gave their lives over the three day engagement, making it the bloodiest single battle of the entire war. The country was tired, weary and wanting the war to end.

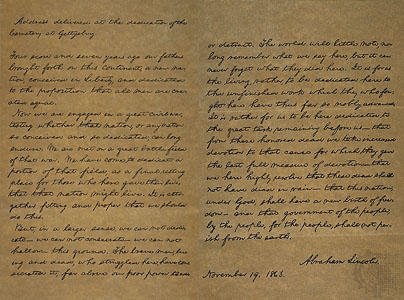

The man who rose shakily to follow the bombast of Mr Everett was, of course, Abraham Lincoln. In sharp contrast, his “remarks” lasted a mere two minutes. Accounts vary but there is some agreement that at the end of his speech there was essentially silence and no rousing burst of applause. Truth be told, it is likely many in the crowd that day did not even have time to register that Mr. Lincoln had begun to speak. The photographer charged with recording the days events was caught so off guard that we have no picture of Lincoln actually speaking. And, Mr. Lincoln himself, slightly stung, perhaps, by the lack of reaction, is said to have remarked to his bodyguard, Mr. Lamon, that “...that speech won't scour...”. An old farmers expression referring to a plow blade that reference to won't do the job.

Mr. Lincoln was not a man to speak lightly or without prepared thought. Indeed, when preparing for a court case as a lawyer, he often would spend hours simply staring out the window of his office, seemingly lost in thought. Those hours were spent searching out what he referred to as the “nub” of the case, or the one fact or circumstance or detail upon which the entire verdict would turn. Later in court, his clients would often panic as he would sit and concede one point after another to the opposing side, seemingly giving away the entire case, only to finally rise at mention of that one particular point or “nub” and hone in on that point so effectively that the day was indeed won handily. In the case of preparing for Gettysburg, some have spread word that Mr. Lincoln arrived unprepared and hastily wrote out his remarks either on the train ride from Washington, or that morning prior to the event. Whether true or not, where and when he put pen to paper matters not at all. We may be assured that the text in form nearly finished existed already within the mind of the president.

Mr. Lincoln was not a man to speak lightly or without prepared thought. Indeed, when preparing for a court case as a lawyer, he often would spend hours simply staring out the window of his office, seemingly lost in thought. Those hours were spent searching out what he referred to as the “nub” of the case, or the one fact or circumstance or detail upon which the entire verdict would turn. Later in court, his clients would often panic as he would sit and concede one point after another to the opposing side, seemingly giving away the entire case, only to finally rise at mention of that one particular point or “nub” and hone in on that point so effectively that the day was indeed won handily. In the case of preparing for Gettysburg, some have spread word that Mr. Lincoln arrived unprepared and hastily wrote out his remarks either on the train ride from Washington, or that morning prior to the event. Whether true or not, where and when he put pen to paper matters not at all. We may be assured that the text in form nearly finished existed already within the mind of the president.

And so he rose that morning to address the crowd, but also, as he certainly knew, to address the nation. His words would, of course, be printed and disseminated across the country within hours if not days.

Politically astute beyond most, Mr. Lincoln was not one to squander an opportunity. The country needed a reason to continue the war to it's ultimate successful (for the nation although not for the South) conclusion. Begun as a war against secession, the conflict now included emancipation of the slaves, a goal not embraced by large numbers in the North, let alone the South. The “nub” behind Mr. Lincoln's intent that day was to reconcile this difference and to provide a new rationale for continuing the war. And the speech he delivered did so masterfully.

The following day, Mr. Everett wrote to Mr. Lincoln complimenting his speech and saying "I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes."

Indeed, despite Mr. Lincoln's fears, the speech did “scour”. It made it's way into the newspapers across the country, inspired a weary nation with new confidence, and has come down to us through history with the judgement of time proclaiming it as one of the finest speeches ever given in the English language.

Not bad for a gangly, self educated country boy from the dusty roads of prairie Illinois. Not bad at all. :-)

Mr. Lincoln remarked in his address “... the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here...”

In this one instance, it appears Mr. Lincoln was uncharacteristically, but happily, completely wrong.

We believe it is important for our children to learn of these events. We believe it is impossible to know what direction to take going forward without a strong understanding of where you have been before. We believe to avoid mistakes in the future it is essential to learn from the mistakes of the past. And so we provide these lessons to our young people through impersonation of some of the finest and most influential individuals America has known – Abraham Lincoln, Benjamin Franklin, Martin Luther King, Thomas Edison, Harriett Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and so on. If you believe as we do that these events still have meaning and the ability to engage the minds of our youth, we hope you will consider allowing us to visit your school with one o our historical school assemblies. We would love to come and see you.

We believe it is important for our children to learn of these events. We believe it is impossible to know what direction to take going forward without a strong understanding of where you have been before. We believe to avoid mistakes in the future it is essential to learn from the mistakes of the past. And so we provide these lessons to our young people through impersonation of some of the finest and most influential individuals America has known – Abraham Lincoln, Benjamin Franklin, Martin Luther King, Thomas Edison, Harriett Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and so on. If you believe as we do that these events still have meaning and the ability to engage the minds of our youth, we hope you will consider allowing us to visit your school with one o our historical school assemblies. We would love to come and see you.

Geoff Beauchamp is the Regional Manager of Mobile Ed Productions where "Education Through Entertainment" has been the guiding principal since 1979. Mobile Ed Productions produces and markets quality educational school assembly programs in the fieldsof science, history, writing, astronomy, natural science, mathematics, character issues and a variety of other curriculum based areas. In addition, Mr. Beauchamp is a professional actor with 30 years of experience in film, television and on stage. He created and still performs occasionally in Mobile Ed's THE LIVING LINCOLN. He also spent ten years coordinating assembly programs for the elementary school where his own children went to school.